Farm accounting can be an incredibly complicated process. Whether you’re an owner, operator, or a dedicated accountant, there are a ton of different costs to track. Also, the long-term market cycle of the agriculture industry demands that farms exercise strict cost controls—trimming the “fat” from the “meat” in all of their expense categories wherever possible.

Your farming business structure and resources—from the farm accounting systems you use to the quality of your soil—are going to be unique. There are countless variables and complications that might render a specific set of practices more or less effective on your farm. This is where opportunity accounting can help your farming business.

Quick Links:

- What Is Opportunity Accounting

- How Opportunity Accounting Transformed Agriculture

- Understanding Cost Behavior for Agricultural Accounting

- Proven Cost Reduction Strategies for Opportunity Accounting

- Get the Agricultural Accounting Data You Need

What Is Opportunity Accounting for Agriculture?

In accounting circles, there’s a concept called “opportunity cost.” Opportunity costs refer to the opportunities, and benefits, missed out on when one alternative is chosen over another.

Opportunity accounting is the practice of assessing your opportunity costs to identify the best business decisions to maximize farm profitability. It weighs the tradeoffs between all of your options to find the biggest possible end benefit for your farm.

The challenge is that costs aren’t always easy to measure—picking one option may mean giving up a chance at making more money, having to spend more on labor, or increasing risk exposure.

Therefore, determining the opportunity cost for each alternative strategy for evaluating the trade-offs between alternatives and help answer the nagging “should’ve, could’ve, would’ve” questions.

Why Separating the “Fat” from the “Muscle” in Your Farm Accounting Books Is Challenging

Whenever your agricultural segment finds itself mired in the trough of a long-term market cycle, cost control has become the “diet of the month” for potentially-bloated farming operations. But which costs represent “fat” and which ones are “muscle?”

- Rents?

- Inputs?

- Equipment?

- Labor?

- Overhead?

Some agricultural opportunity costs are easy to estimate, particularly those tied to production coefficients. These make it simpler to set and achieve farm management goals.

However, the process gets murkier when evaluating changes that affect indirect and/or fixed costs, such as keeping versus “rolling” new machinery every year. Cash payments and annual depreciation may go down, and repairs will likely go up. Meanwhile, you may also have dropped or picked up a farm or two—affecting the acres you are spreading fixed costs against.

Once you start tweaking assumptions and allocations beyond direct costs, you’ll discover your operation is made up of many related “moving parts” that defy “quick and dirty” spreadsheet analysis. If your plans involve changing or reallocating numerators (dollars) as well as denominators (acres, hours, machinery capacity) then you’ll be playing an Excel version of “Whack-A-Mole” as new costs pop up in one cell as you push expenses down in another.

The biggest limitation of this cost control strategy, however, has to do with your assumptions. If you don’t already have a good handle on the unique mix of fixed and variable costs going on within each activity in your operation, you won’t know which processes are lean and efficient and which could be the “biggest losers.”

How Opportunity Accounting Transformed Agriculture

If opportunity cost accounting is such a challenge, why is it worth pursuing? Let’s take a quick look at the history of the practice to see how it has transformed the agriculture industry.

Over the past hundred years North American agriculture has transformed from a diversified to specialized production model. The hen house, milk cow, and moldboard-plowed corn-oats-meadow rotation have been replaced by fence row-to-fence row monoculture, site-specific management and concentrated animal feeding operations.

Where we are today is due to a nearly infinite series of decisions that evaluated the trade-offs between maintaining, expanding, or eliminating enterprises and in sourcing or outsourcing various farm services.

The pork industry provides an instructive example of that transition:

- 1900-1970: mostly outdoor, single-site farrow-to-finish consuming raised grain

- 1970-2000: controlled-environment, single-site farrow-to-finish with on-site feed mill

- 2000-Present: large-scale, bio-secure, independently owned/managed, multi-site boar stud, breeding and finishing serviced by a central feed mill

This was accomplished not by a top-down, corporate edict but through a process of trial-and-error experiments that demonstrated that costs and risks could be reduced by adopting what appeared to be counter-intuitive strategies (transitioning pork production from single-site to geographically-dispersed business segments). Production models that initially appeared ideal on paper (mega-growth at a single site) proved to be less efficient and profitable when the accounting results were tallied.

In situations like this the economic opportunity costs of adopting (or not adopting) a new practice are unknown because either:

- Not enough experiments have been run to predict the response; or

- The results are too dependent on the unique variables within an operation.

Fortunately, American agriculture is constantly reinventing itself thanks to an endless parade of innovators probing the boundaries of production and efficiency and turning conventional wisdom on its head—often launching new ag tech trends. Opportunities manifest themselves through countless inventions, networking, borrowing ideas from other industries and leveraging knowledge.

Modern farm accountants, owners, and operators can benefit from the use of agricultural accounting software that provides them with real-time data from across all of the farm’s varied enterprises. This makes it easier to get an accurate, up-to-date picture of the health of the whole farming operation and the impacts of various choices—speeding up the cost-benefit analysis of different operational choices.

Understanding Cost Behavior for Agricultural Accounting

High commodity prices are a mixed blessing. On the one hand, they provide prosperity that “lifts all boats” for the producers growing those crops. On the other hand, good markets mask inefficiencies that can come back to haunt farmers when times get tough.

When the only game in town is cost control, your options are rarely quick or simple—and some may potentially be counter-productive.

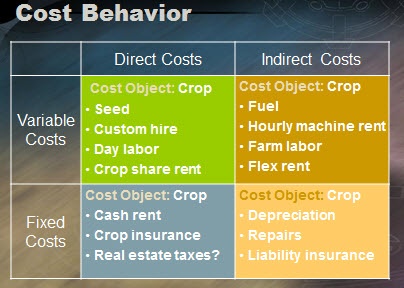

It’s important to recognize there are four ways of categorizing costs: direct, indirect, variable, and fixed. These cost categories can be divided into two opposing sets: direct vs indirect and variable vs fixed.

Direct vs. Indirect Costs

Direct costs can be traced to a cost object in an economically feasible way while indirect costs cannot. A cost object is anything for which a measurement of cost is desired.

For example, if your cost object is a corn crop then your seed, chemicals and fertilizer would be included in direct costs while your equipment would be considered as an indirect cost.

Note that “economically feasible” (tracing) is the determining factor between direct and indirect costs. For instance, an off-season tractor repair bill is hard to trace (and frustrating to allocate) to the crops the tractor will be used on during the farming season. On the other hand, specifically-identified seed inventories can be feasibly traced to the farms and crops where they are planted.

Variable vs. Fixed Costs

The defining difference between variable and fixed costs is that Variable costs change in proportion to changes in the related level of activity or volume, but fixed costs remain unchanged in total for a given time period despite wide changes in the related level of total activity or volume.

For example, feed and per-acre custom farming charges are instances of variable costs in production agriculture. Depreciation and cash rent are examples of fixed costs.

So, are all direct costs variable, and are all indirect costs fixed? The exceptions make farm opportunity accounting interesting.

- Day labor hired specifically to harvest a vegetable crop is both variable and direct, but full-time farm employees informally allocated to various jobs are often treated as indirect costs.

- Annual cash rent is a fixed direct cost, crop share rents are direct variable costs and “flex” rents incorporate indirect costs behaviors from external costs and/or market adjustments.

- Farmers can treat fuel either as an indirect cost allocated "after the fact" or as a direct variable cost tied to specific field production activities.

- Real estate taxes can be either a direct fixed cost or an indirect fixed cost depending on how they flow through a land entity.

- “Arms-length” services like custom farming and contract livestock production transform indirect fixed costs into direct variable and fixed costs.

This table illustrates the relationships and examples among these cost categories.

Proven Cost Reduction Strategies for Opportunity Accounting

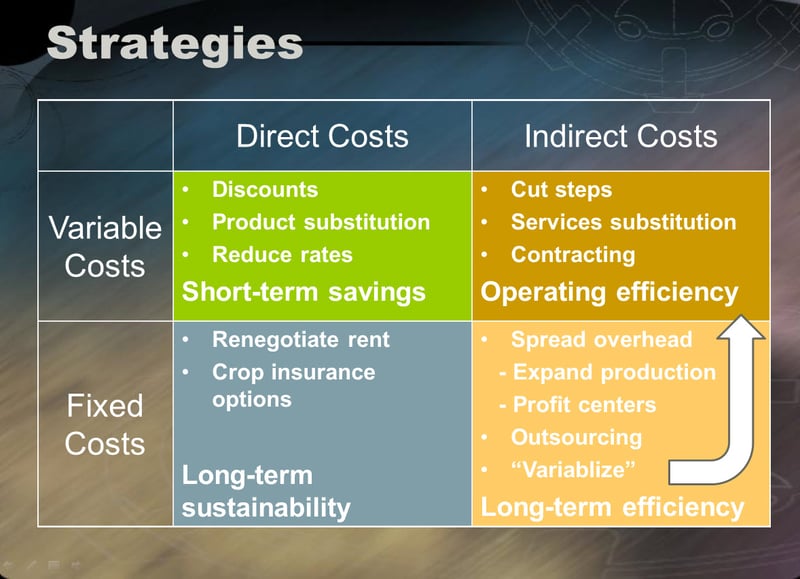

Direct variable costs such as crop inputs receive the most attention in the farm press and coffee shop because they’re the largest segment of production costs, are relatively easy to measure and are subject to “comparison shopping.” The strategies for cost reduction are tried and true: volume purchasing, off-label or generic products, reduced application rates, switching to less cost-intensive crops. While significant cost savings are possible, keep in mind every other sharp manager is likely following this same practice. Also, keep in mind that while reduced out-of-pocket spending is easy to measure, the hidden costs of lowered production are harder to determine.

Indirect variable costs that include fuel, labor, hourly machine rent and flex land rent require a little more analysis. The strategy here is to increase operating efficiency either by lowering outlays for these indirect costs, increasing production with the same investment, or both. It’s possible to accomplish a few short-term “tweaks” in labor or machine hire by cutting steps or employing cheaper alternatives; however most of the opportunities for reducing indirect variable costs are long-term (switching to contract labor or renegotiating flex rents).

Direct fixed costs encompass cash rents, crop insurance and real estate taxes. Most of the emphasis these days is to renegotiate or walk away from unsustainable cash rents that were so willingly bid up in more exuberant times. Various crop insurance options provide out-of-pocket premium savings but may not be the best alternative if claims are likely. Unfortunately, real estate taxes are uncontrollable.

Indirect fixed costs are capital-intensive farming’s “boat anchors,” but they can be reduced…indirectly. Repairs can be “traded” for newer equipment or you can “live off of depreciation” (in the short run) by not replacing equipment while hoarding cash. Here are some better strategies to manage and reduce those burdensome fixed costs:

- Spread fixed costs over more output. Many operations are high-cost producers because their overhead (general & administrative, management team, equipment and facilities) is oversized for their production base. However, if they are able to efficiently replicate their management and control processes over expanded acres or animals then they can drive down overhead per-unit costs.

- Turn excess capacity into a profit center. An alternative to internal growth is to allocate fixed costs to external services like custom farming, trucking or scouting, spreading overhead over more units and reducing production risks by diversifying.

- Outsource services are the mirror image of the previous strategy. You negotiate with a neighbor or business that will perform services like spraying, harvesting or trucking more cost-effectively than you can and you shed excessive equipment and labor.

- “Variabilize” fixed machinery costs (particularly combined) by leasing. This was one of financial consultant Moe Russell’s recurring themes at the FBS User Conference.

Once you’ve exhausted the obvious cost-cutting strategies—squeezing input suppliers, coming hat-in-hand to landlords or living off of depreciation—it’s time to discover the untapped opportunities hidden in fixed costs.

In the USDA’s Farm Production Expenditures 2020 Summary, the costs related to farm equipment costs were a major part of U.S. farm’s operating costs in 2020. The equipment-related costs in the report included:

- Fuel. $11,100,000,000.

- Tractors and Self-Propelled Farm Machinery. $13,700,000,000.

- Other Farm Machinery. $6,000,000,000.

- Trucks and Autos. $5,100,000,000.

Collectively, these equipment costs accounted for $35,900,000,000 out of a total of $366,200,000,000 spent on production expenditures in 2020—roughly 10.2% of all the money spent on farm production that year.

Not only are equipment costs significant, they also vary widely from farm to farm. "There still is a fixed cost out there no matter what you do, so the incentive is to go out there and get the variable cost covered and eat into the fixed cost," says Gary Schnitkey, a University of Illinois economist.

Nonetheless, being aware of aggregate overhead, labor and machinery costs is not the same as managing those costs or understanding in which activities you are efficient (and should expand to drive down costs) and in which ones you are inefficient (and should outsource).

Get the Agriculture Accounting Data You Need to Identify Opportunity Costs

To pull off opportunity accounting, you need to have accurate, up-to-date data about your whole farming operation. Being able to track costs and profits for all of your farming enterprises is critical for accurately assessing the opportunity costs associated with each of them.

FBS Systems offers comprehensive agricultural accounting solutions complete with service and support to help you get all of the data you need to make the most informed decisions to fuel your opportunity accounting strategy.

Reach out to us today to discuss your needs and discover how you can empower your ag accounting.